urbanmakers

Our name urbanmakers reflects our commitment to creating a city that is rich in human interaction, attentive to social balance, beautiful and sustainable.

Our practice is rooted in the observation of traces of the past, the development of unifying narratives and the construction of harmonious realities. The agency’s projects share the same philosophy: to design architecture that is contextual, sober and generous.

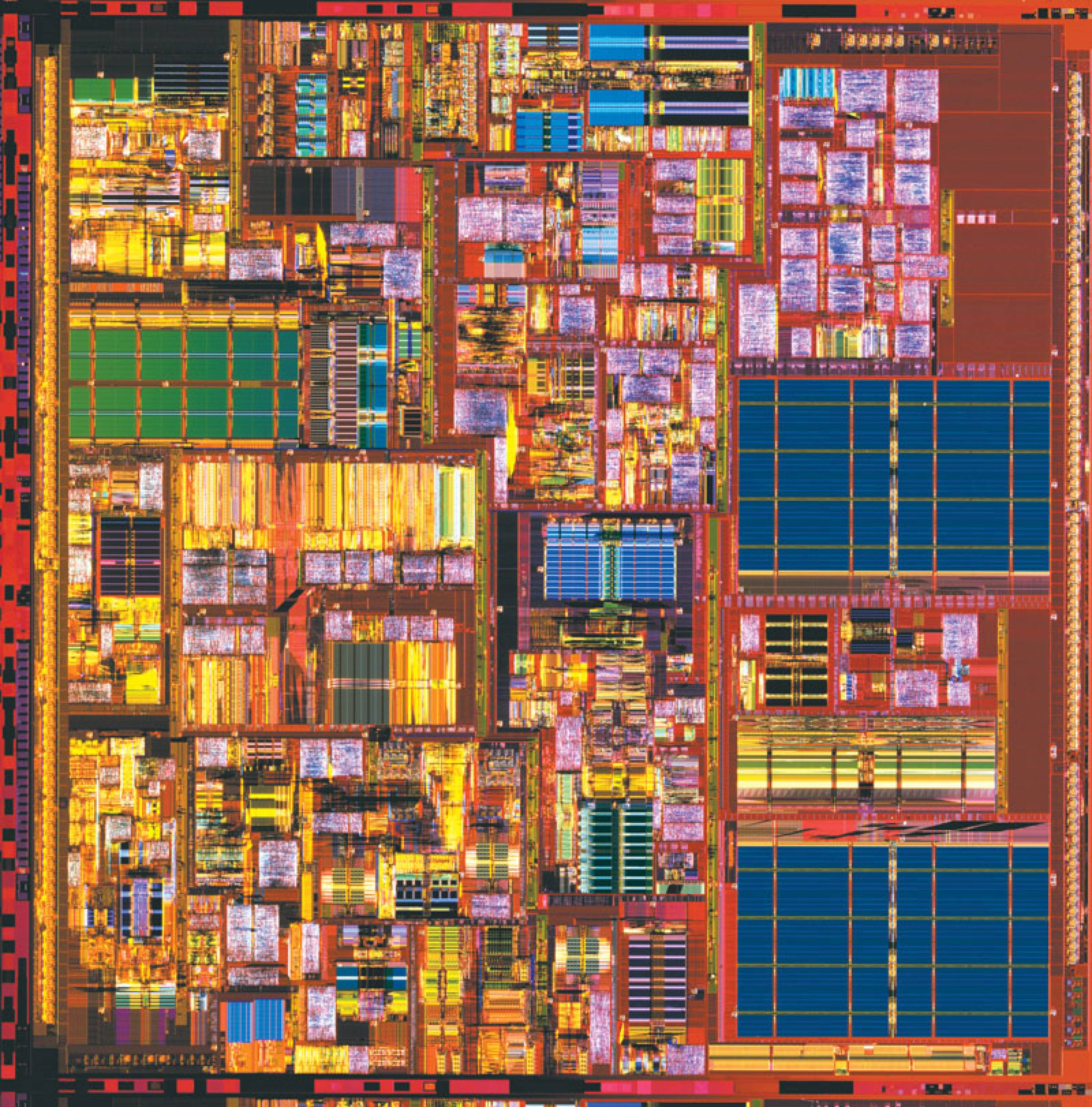

In the face of climate upheaval, we are working on new hybrid construction processes, in particular using natural materials, limiting the use of concrete, and our excellent mastery of BIM.

[Fig.1] Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1927

[Fig.1] Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1927 However, the cold drove them together again, when just the same thing happened. At last, after many turns of huddling and dispersing, they discovered that they would be best off by remaining at a little distance from one another. »

Arthur Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena (1851)

Housing, on the other hand, has a completely different scope, with an emotional and sensory dimension. It suggests a way of living, a place and the possibility of adopting it.

An inhabitant makes the space he lives in his own: he furnishes it, he creates his own world, defines a universe that resembles him and bears his imprint. Because a place is fully inhabited when it is possible to express your own singularity.

Thus, isn’t it our role as architects to inscribe the conditions of this hospitality in the space? When dealing with the issue of square metres and the formatting of programs, isn’t the challenge to leave free space, emptiness, space for play so as to allow the inhabitant to play with his place by himself?

This experience of hospitality is made up of a multitude of details. Some of them are obviously related to the layout of the accommodation itself: positioning of the load-bearing walls, clever distribution, retractable walls, doorways, double height, extensions towards the outside…

Others are more about design: window sills, shelves, wide steps, niche, functionality of a storage unit, etc.

The key to success lies is the good connection between all these arrangements: even if the space is sober, it can still evoke emotions and a sense of well-being.

Moreover, housing induces a double polarity: the inner sphere of the “home” and that of the common spaces of the “being together”. Being able to fully inhabit one’s home is just as important as enjoying shared spaces.

Caring for passageways, placing in them the same invitations for appropriation as those in private spaces, are the result of a staging process that encourages encounters. Thus, every place that is usually considered purely technical in the life of a building can be seen as a place that encourages neighbourhood moments, as an opportunity to create a community. A car park becomes a place for carpooling, an entrance hall houses a temporary market, a bin storage area offers community compost, all are signs of a collective commitment in a sustainable way of life. The space devoted to letterboxes allows the display of possibilities for mutual aid between neighbours, in a game of request and offers for services. As for the bike storage rooms, they become real workshops for tinkering and repairing together.

Each of our initiatives thus aims to represent the theatre of a fulfilled everyday life: our work will fully make sense if it provides well-being to the people who live in our buildings.

In practice, improving the quality of the neighbourhood means an increase in vertical circulation. At first glance, this solution is incompatible with the control of rental charges (due to the large number of lifts). However, it guarantees the long-term durability of the spaces and eases maintenance and security.

In the end, everyone takes greater care of the shared building.

As a result of this organisation, there are more entrance halls, the feet of the buildings are livelier. The strategy of a small neighbourhood extended on the upper floors thus brings greater urbanity at ground level and in public spaces. Multiplying the number of entrance halls makes it possible to better distribute the premises dedicated to cycles: they are placed on the daily routes; the use of bicycles also becomes more intuitive.

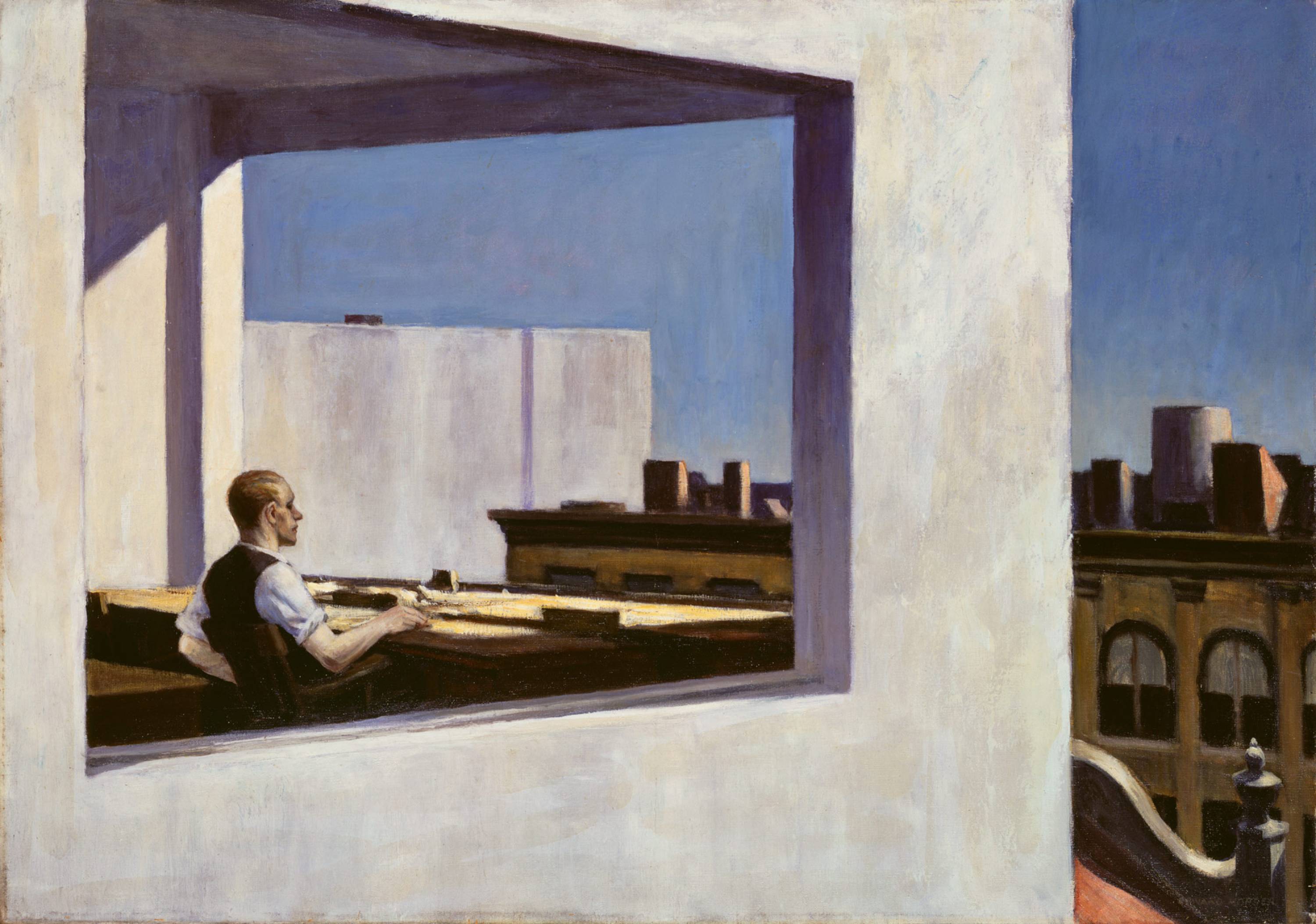

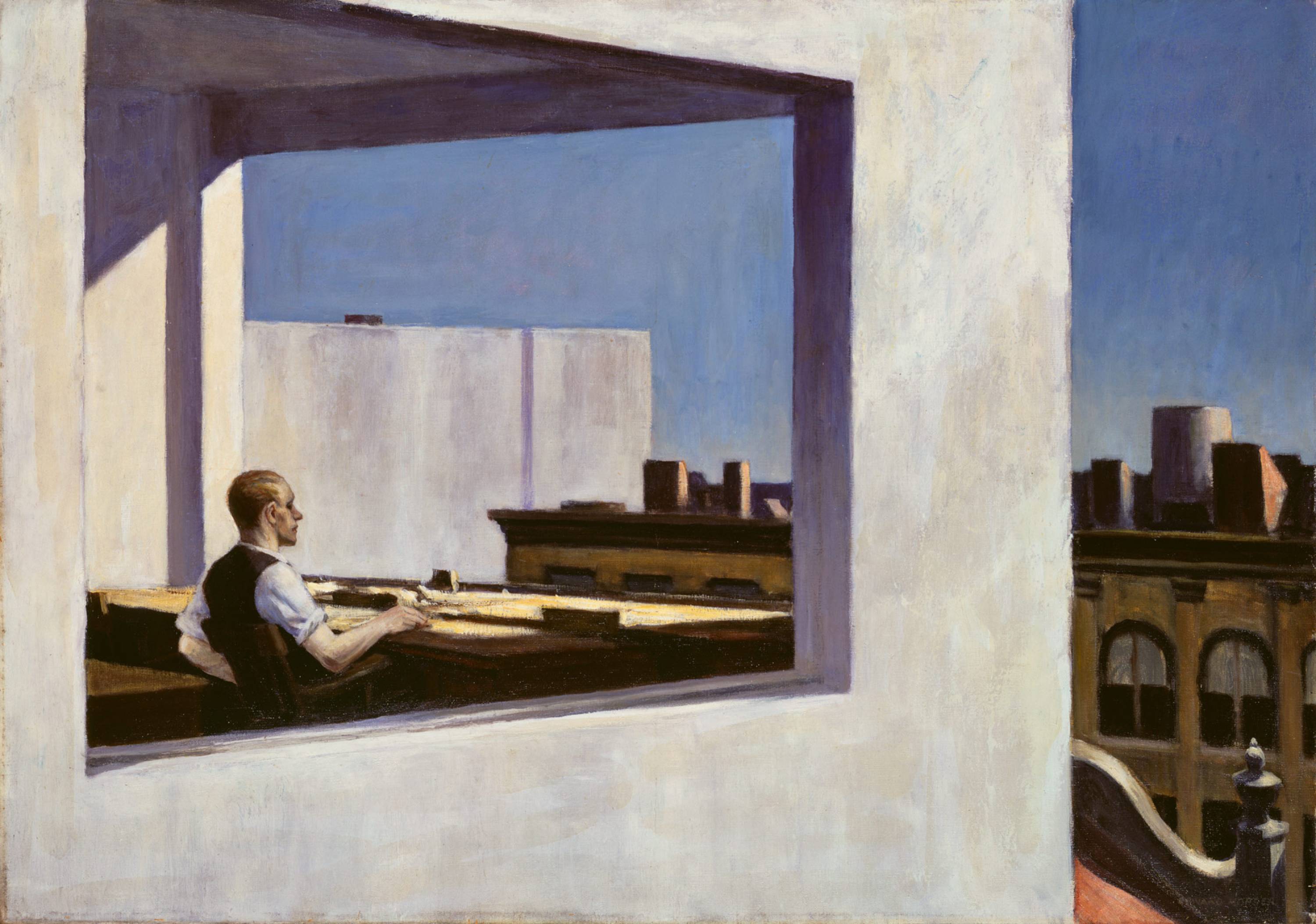

Directly associated to the well-being of the inhabitants, the window is the ingenious, geometric, architectural and artistic reply to this need for light. This is the reason why we like them generous, sometimes oversized. The window, like the balcony, opens onto the world. It projects us into urban life, it offers to be part of the hustle and bustle of city life while remaining at a distance, being there without being there. The window is the emptiness which makes it possible to link the inside and the outside.

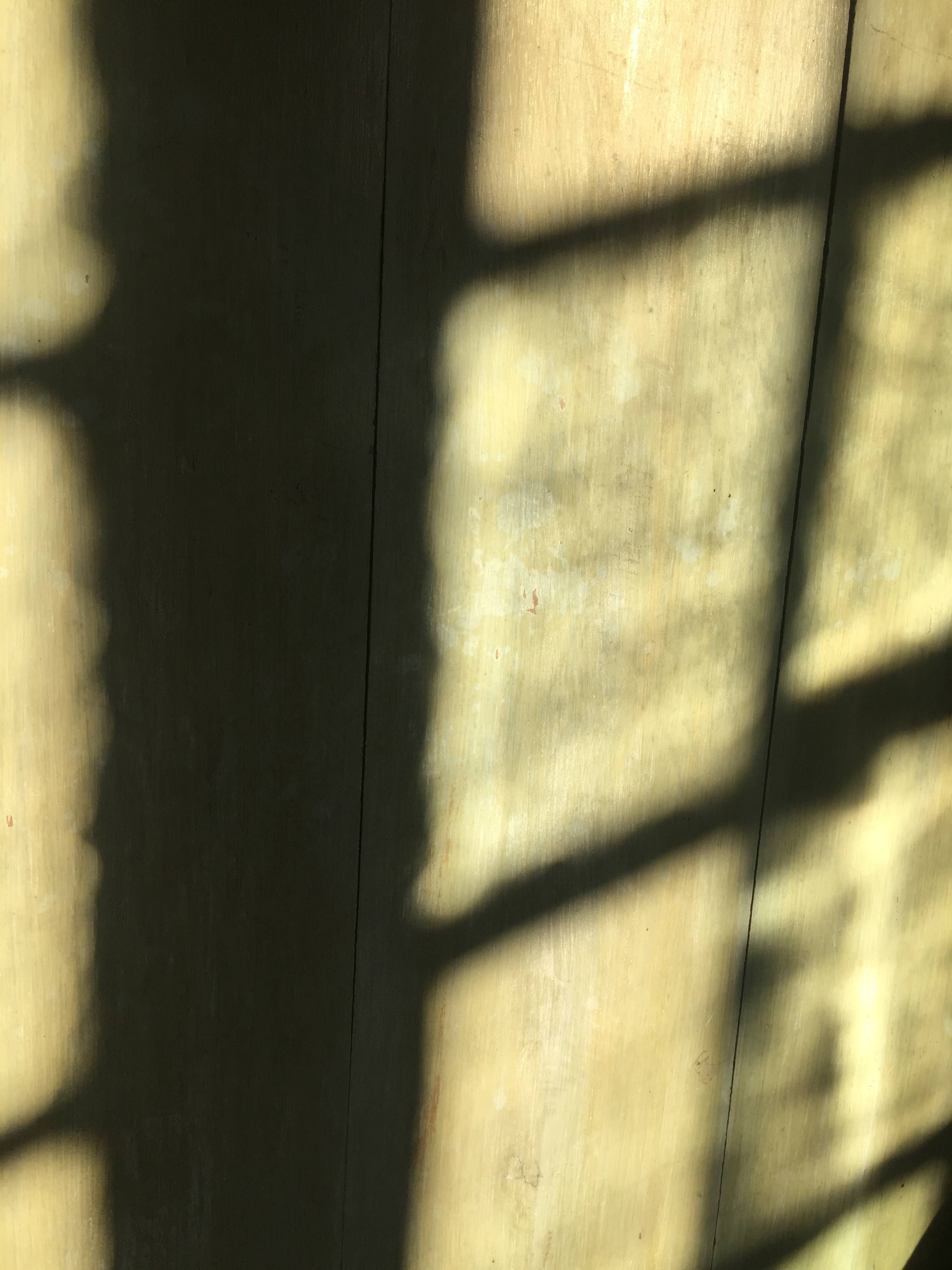

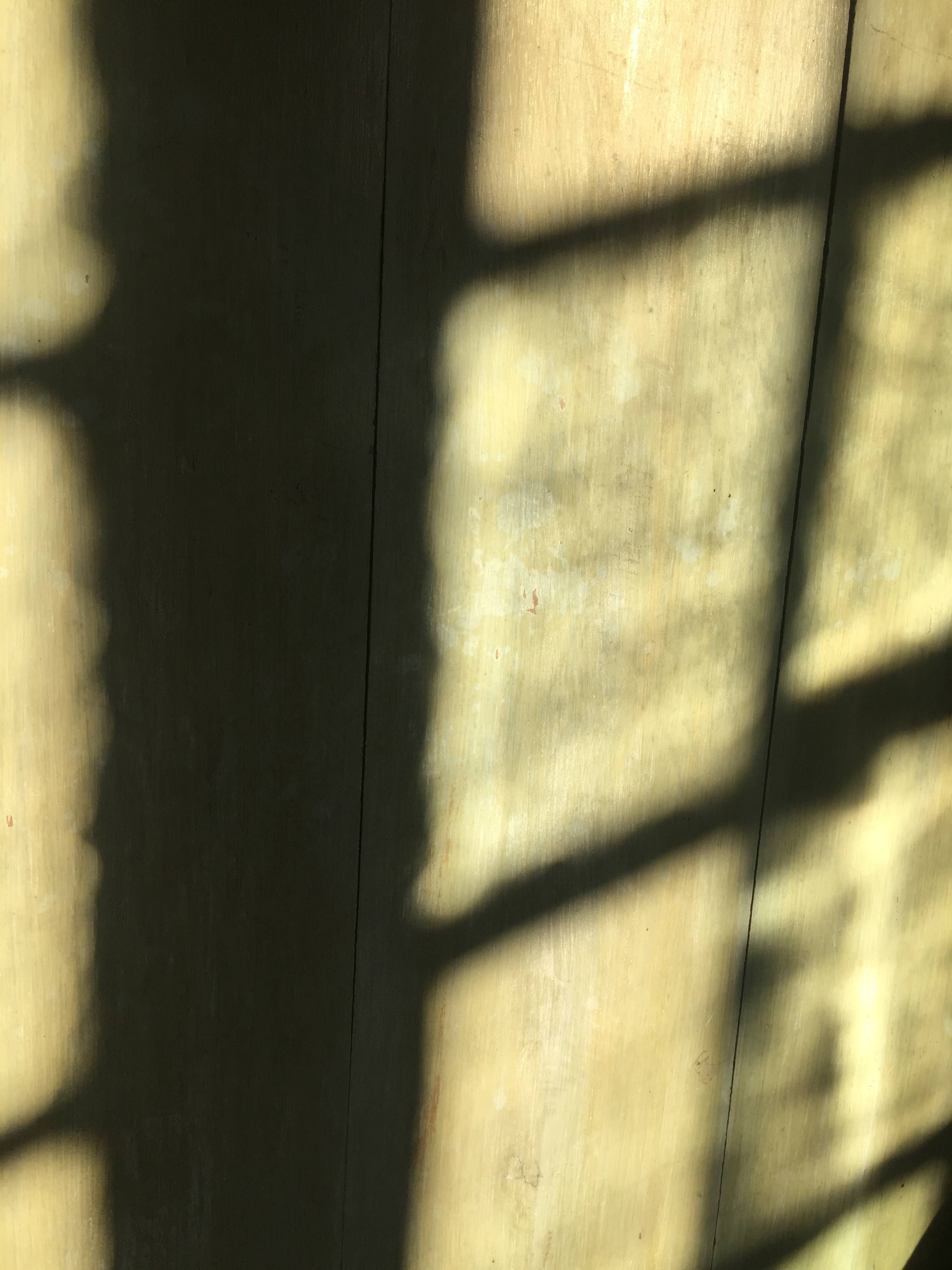

But emptiness always leads to fullness and light calls for shadow. Even if we have a crucial need for light, we must also be in a position to escape from it, to distance ourselves from the light and withdraw into our intimacy. A space is serenely inhabited when it is both open and secure, illuminated and shaded at the same time. Our extreme vigilance regarding the views also obeys this rhetoric of the shadow, so that the gaze of one cannot damage the intimacy of the other. How many balconies and frontages have been disfigured by uncontrolled filters installed for lack of privacy?

This is the role of the spandrels, railings and privacy screens, these architectural elements that require the utmost precision. We work on their opacity and proportions to let the view out while protecting from the gaze of passers-by.

From this point of view, the loggia is another interesting option: this recessed space expands the living space, becoming a real extension of the living rooms on the outside. As it is cosy and protected it can be used for many mid-season purposes.

Preventing the storage of items seems illusory to us: it is more appropriate to create external storage solutions integrated into the architecture. The standing of the building must be preserved over time.

This dialectic between light and shadow leads to a wider perspective with regard to the notion of hospitality. Creating a space that lets you open up to others and welcome them at home involves these variations of light and shadow. All these elements give food for thought on the most accurate way to design spaces that are both intimate and hospitable at the same time.

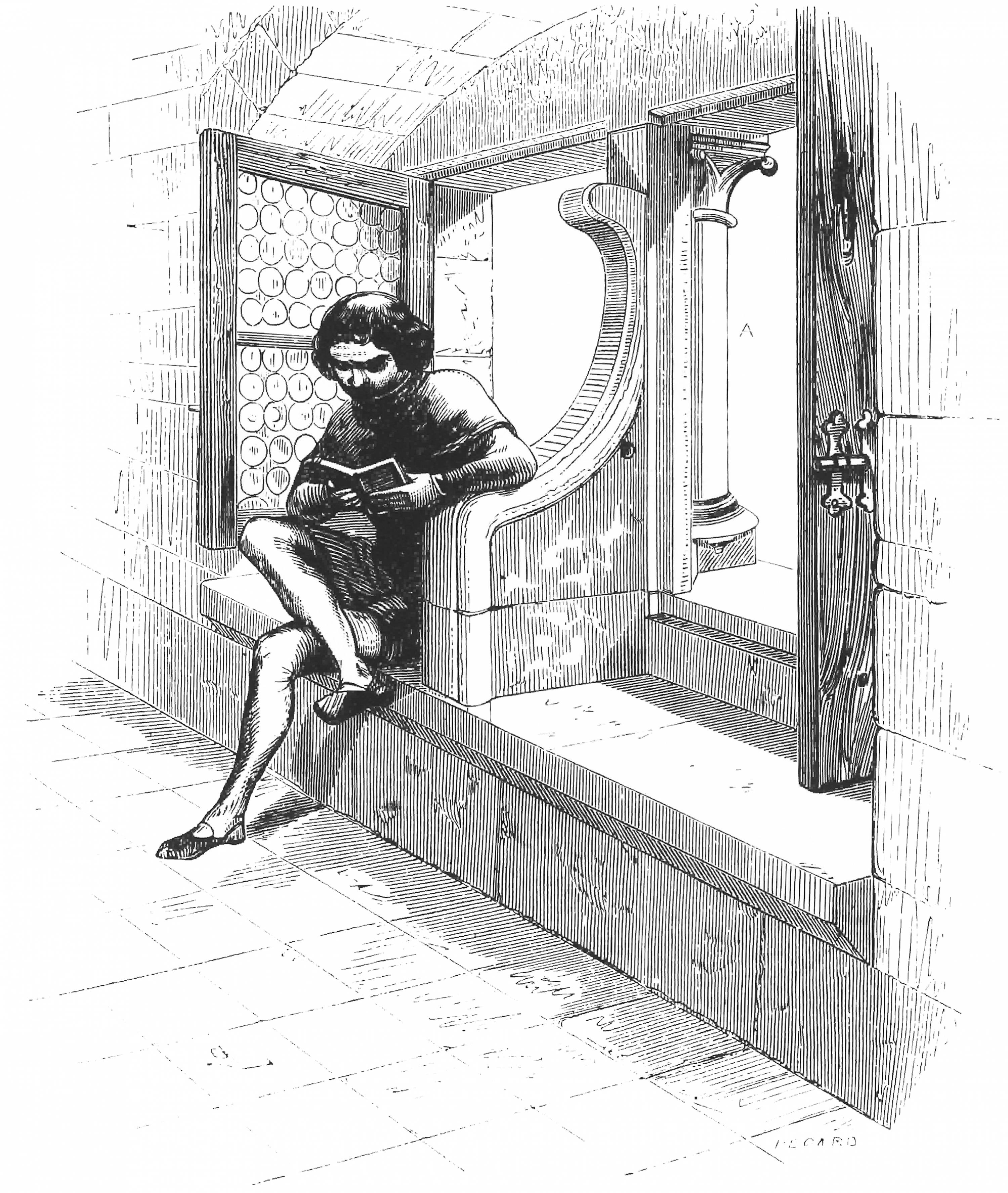

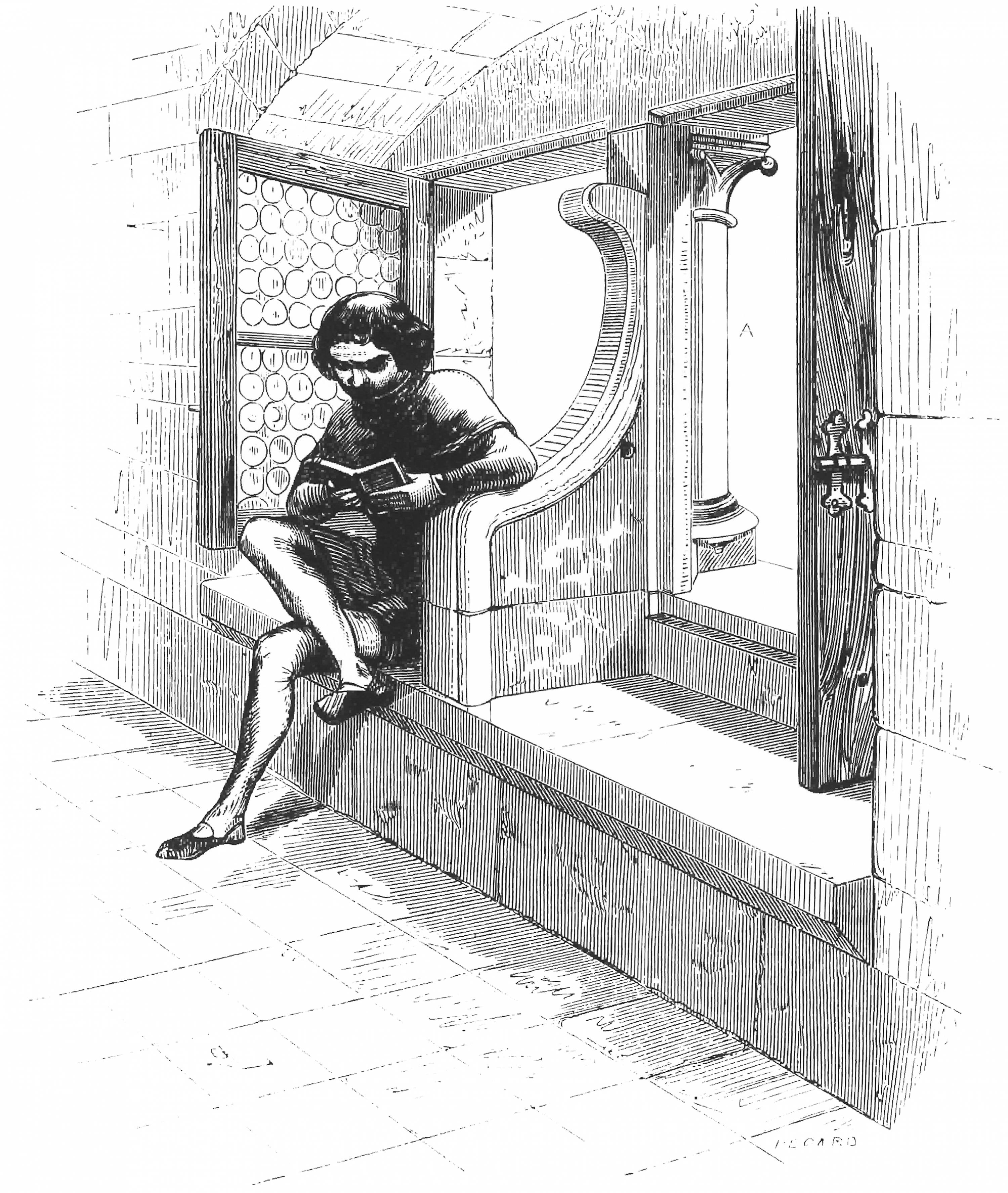

The window expresses the world of interiors, it is particularly rich when it is deep, in the thickness of the wall. It becomes a living space where you can develop your personality, it can be turned into a shelf, a library, a miniature garden… Designed as an alcove, it will be an ideal space for contemplation or reading (like the medieval openings created in the depth of the walls, that were so poetic.

From the outside, the window gives the human dimension of the city. By looking at the windows from the street, you can evaluate the degree of hospitality of the place. “It attracts the eyes, intrigues the spectators, arouses desire. The window has everything you need to build a plot, to imagine a story, to write a whole novel 1.” From this perspective, don’t you think we can say that the window is the raw material of city architecture?

1. Pascal Dethurens, L’œil du monde (Ed L’atelier contemporain).

Windows are condensed examples of architecture; they are unlimited sources of expression and poetry: we are passionate about assimilating all their historical and regional codes. It is therefore important for us to qualify their shapes (slender curve, majestic severity, patriarchal harmony, etc.) and their vocabulary (entablatures, lintels and sills, shutters and blinds, mantling, interior panels, espagnolettes, transoms and mullions, etc.)

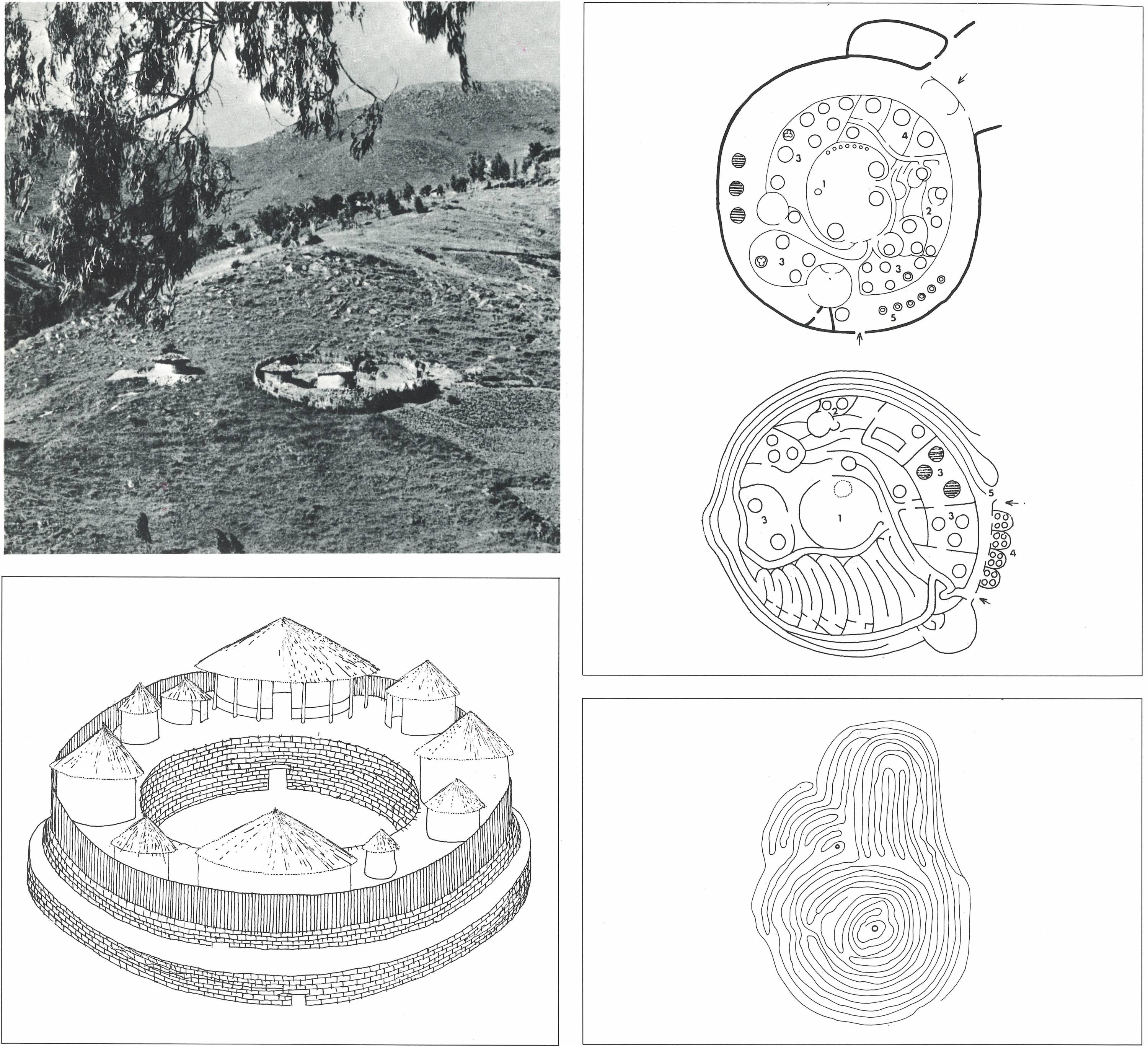

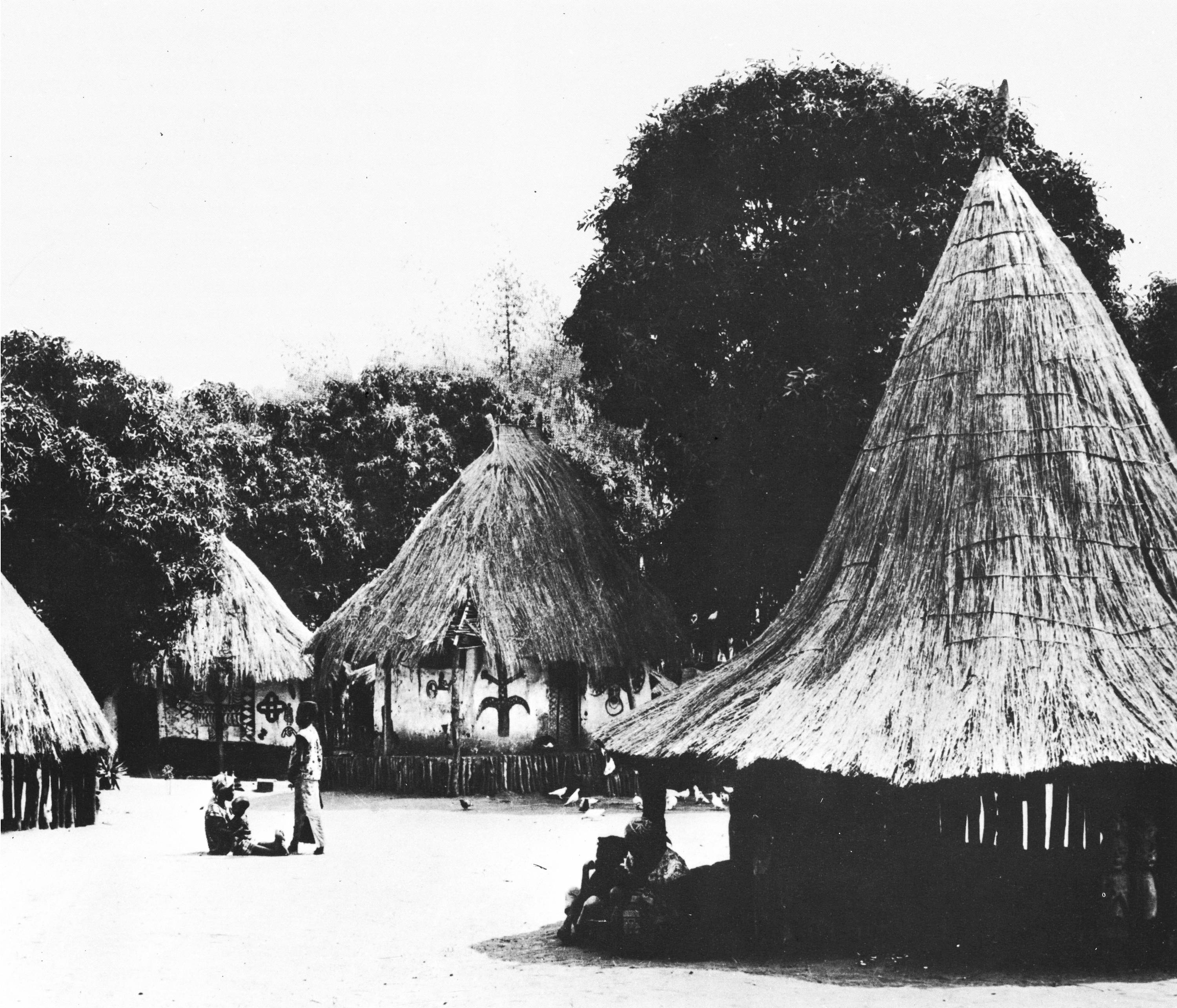

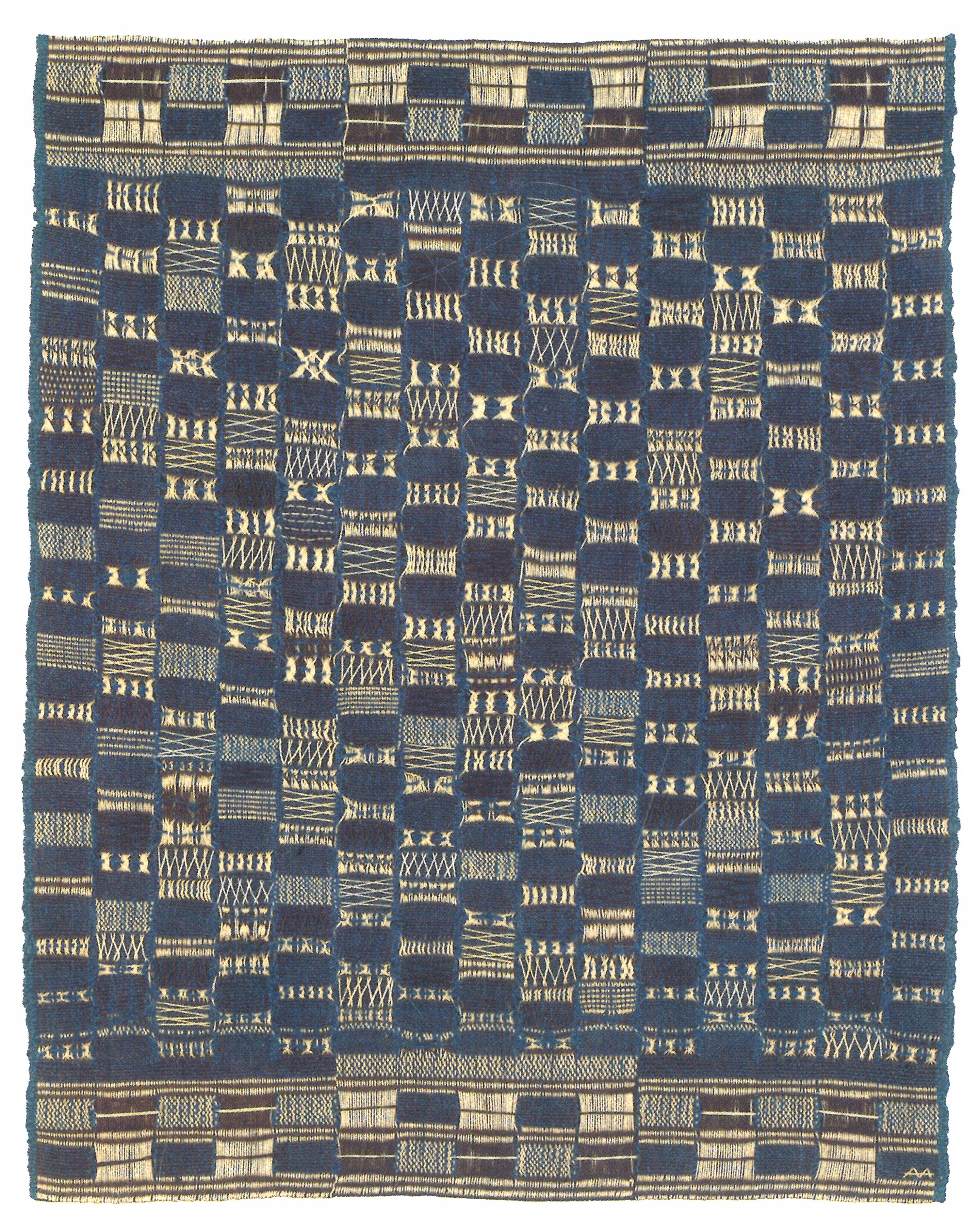

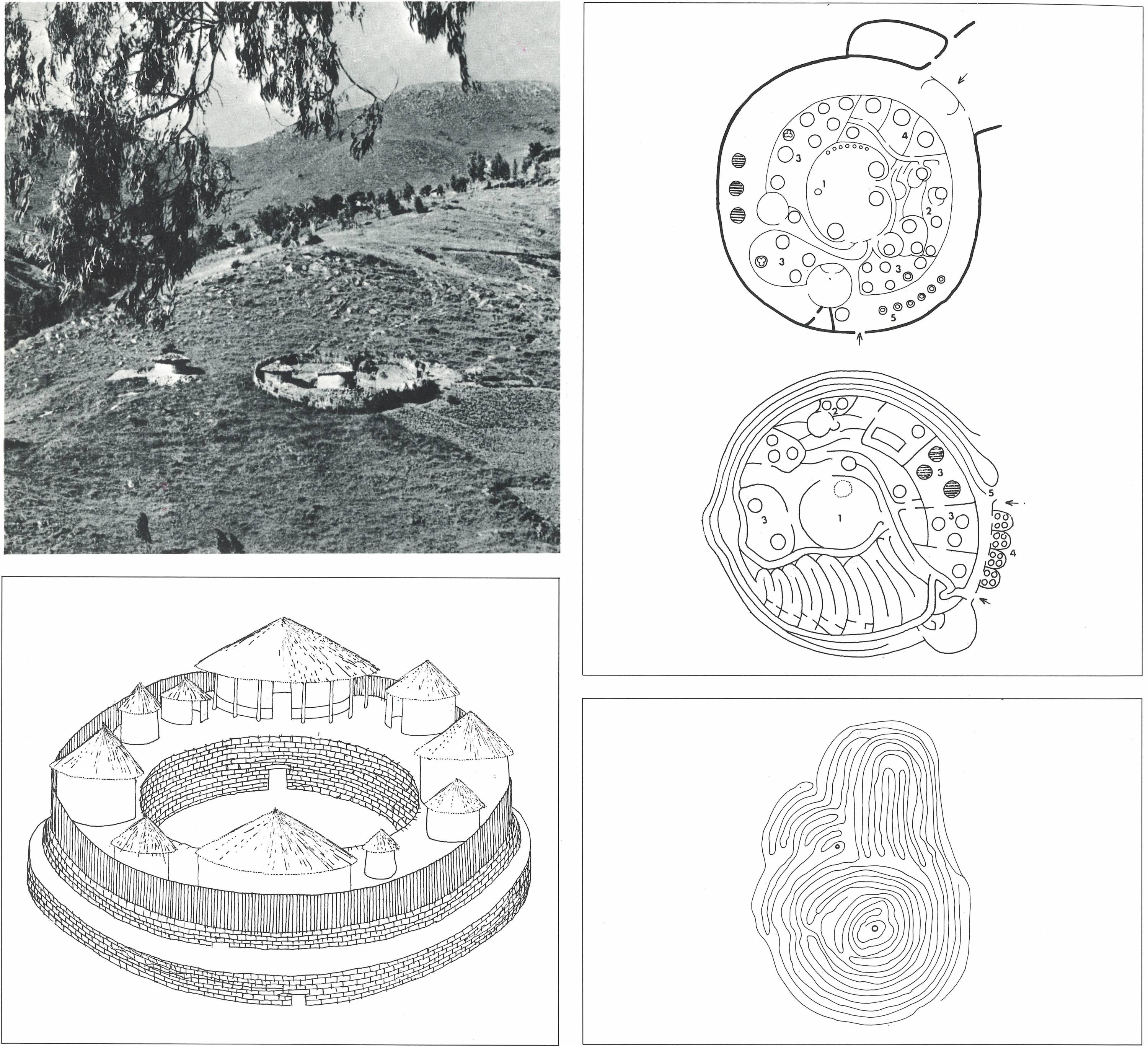

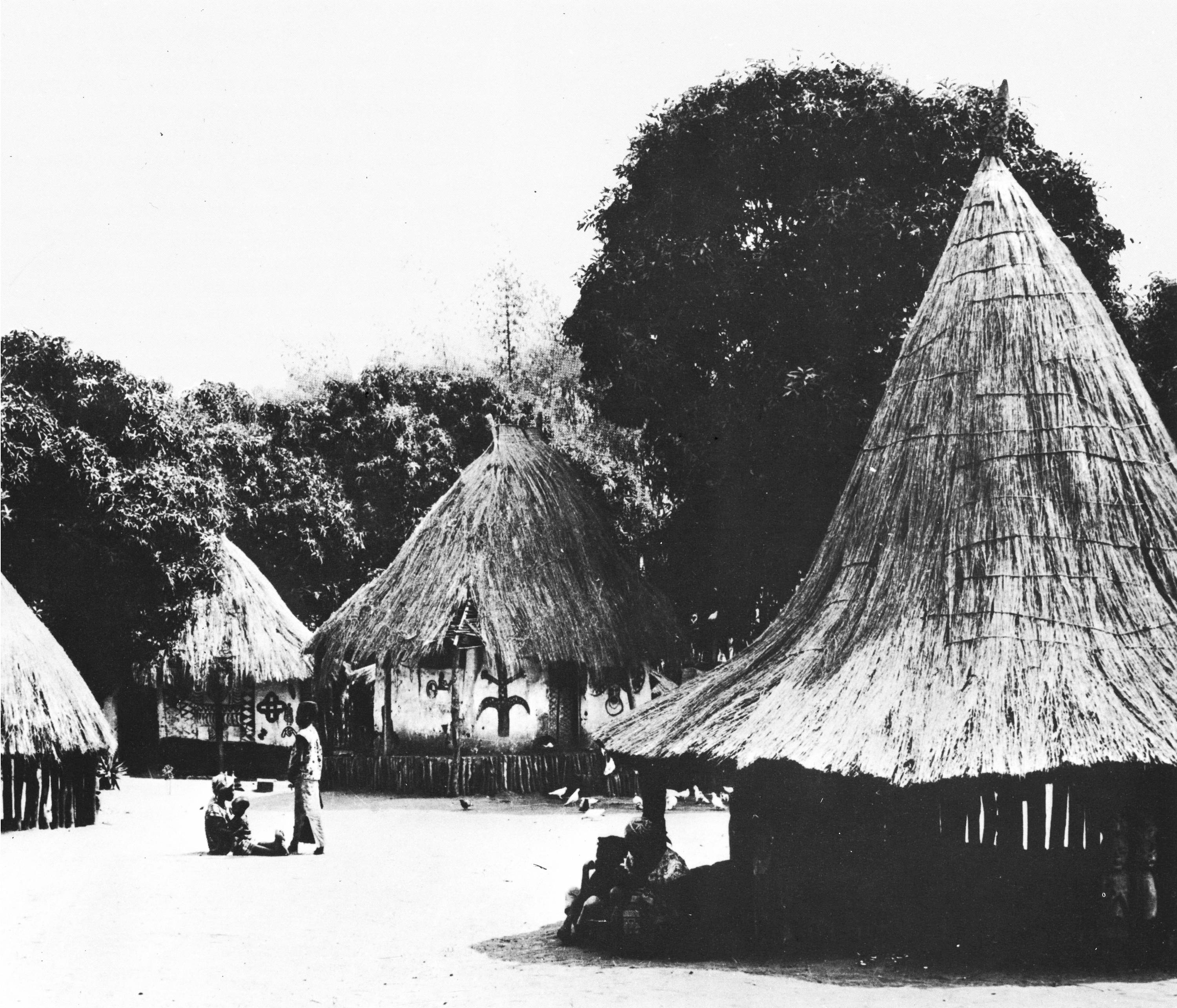

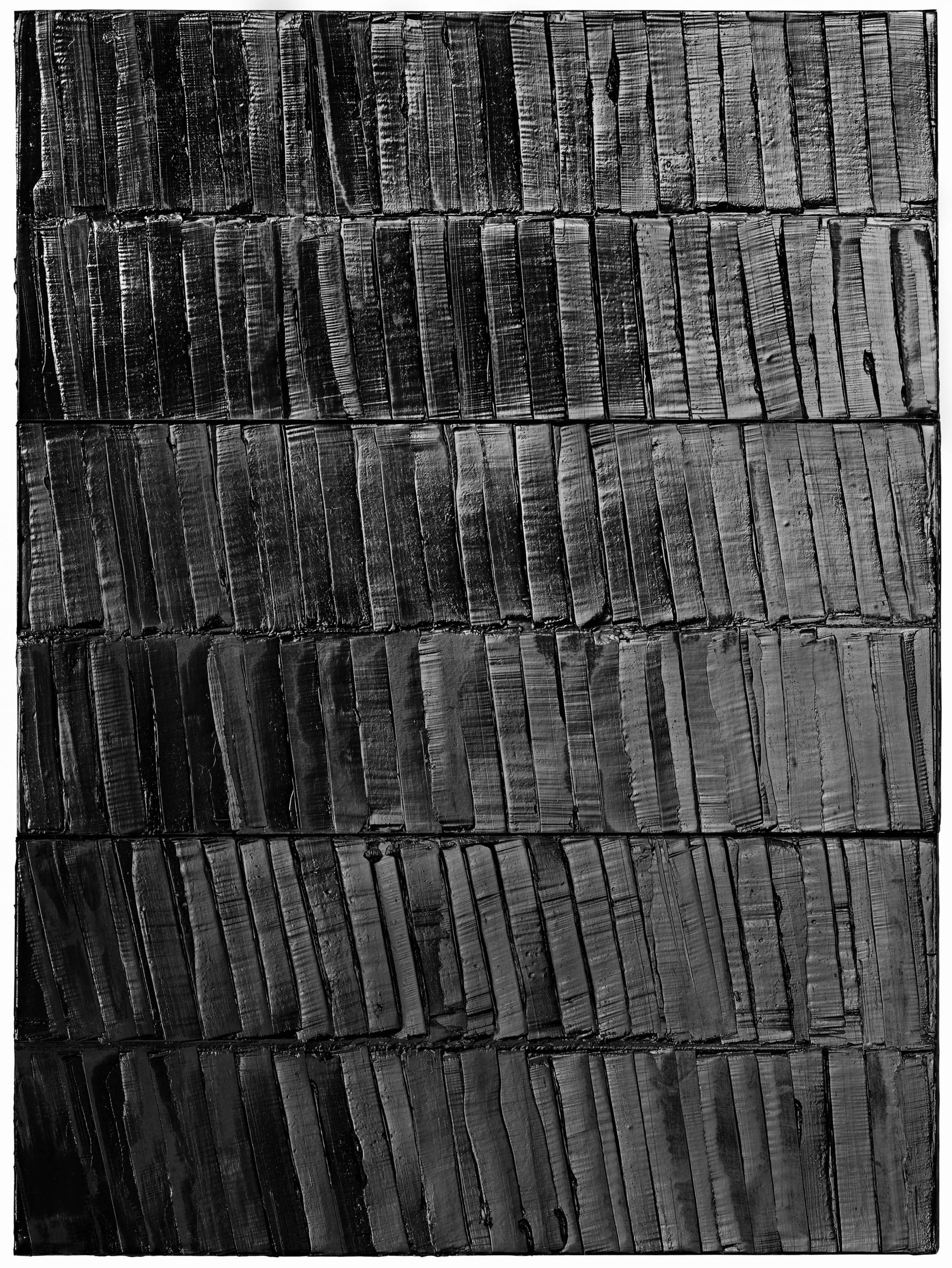

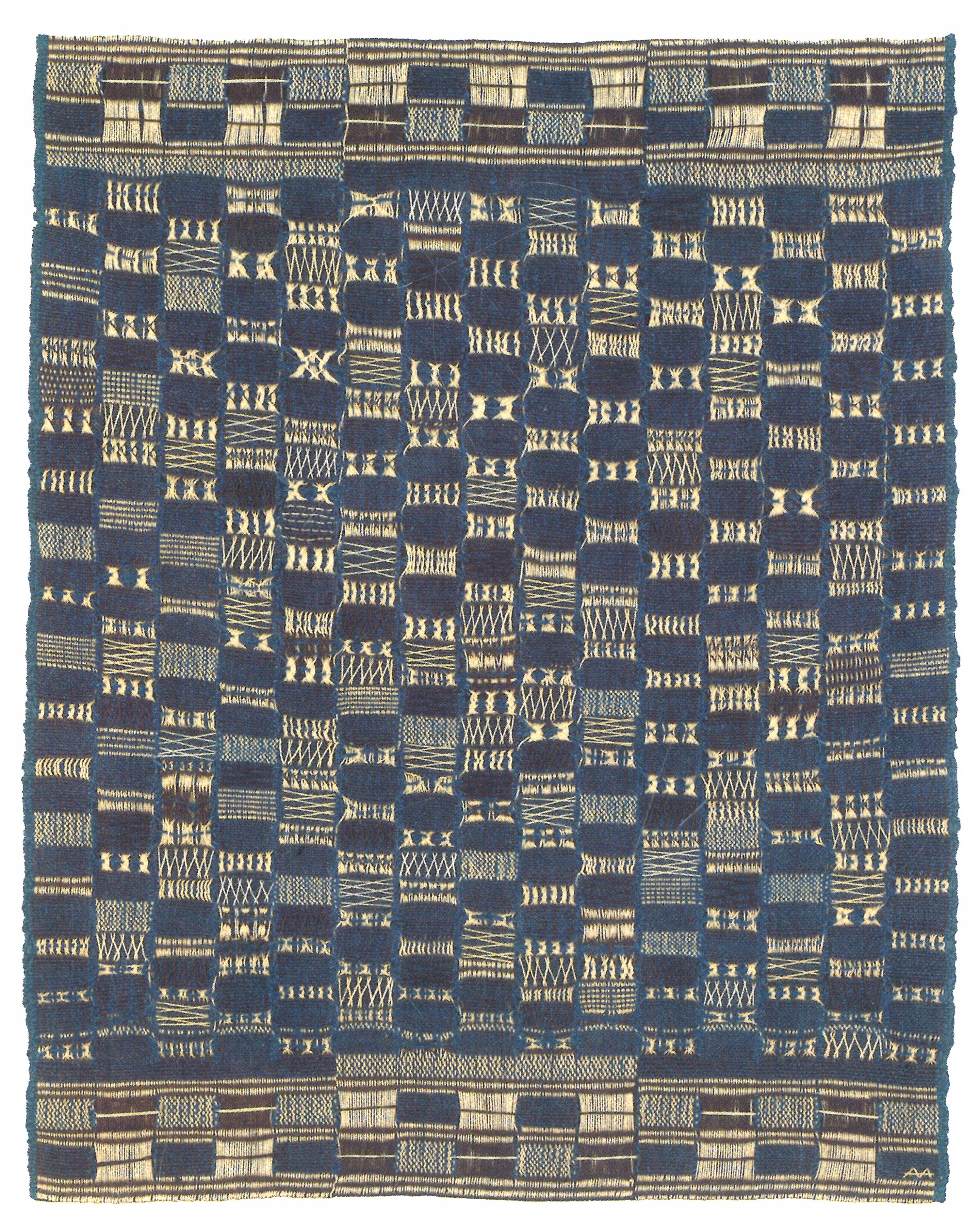

. In this respect, materials are very significant: they evoke the specificity of a place or a function and they bring a symbolic and aesthetic dimension that is specific to each time period. For example, you can recognise the use of stone typical of a region, noble materials for an important building or more common materials for vernacular housing.

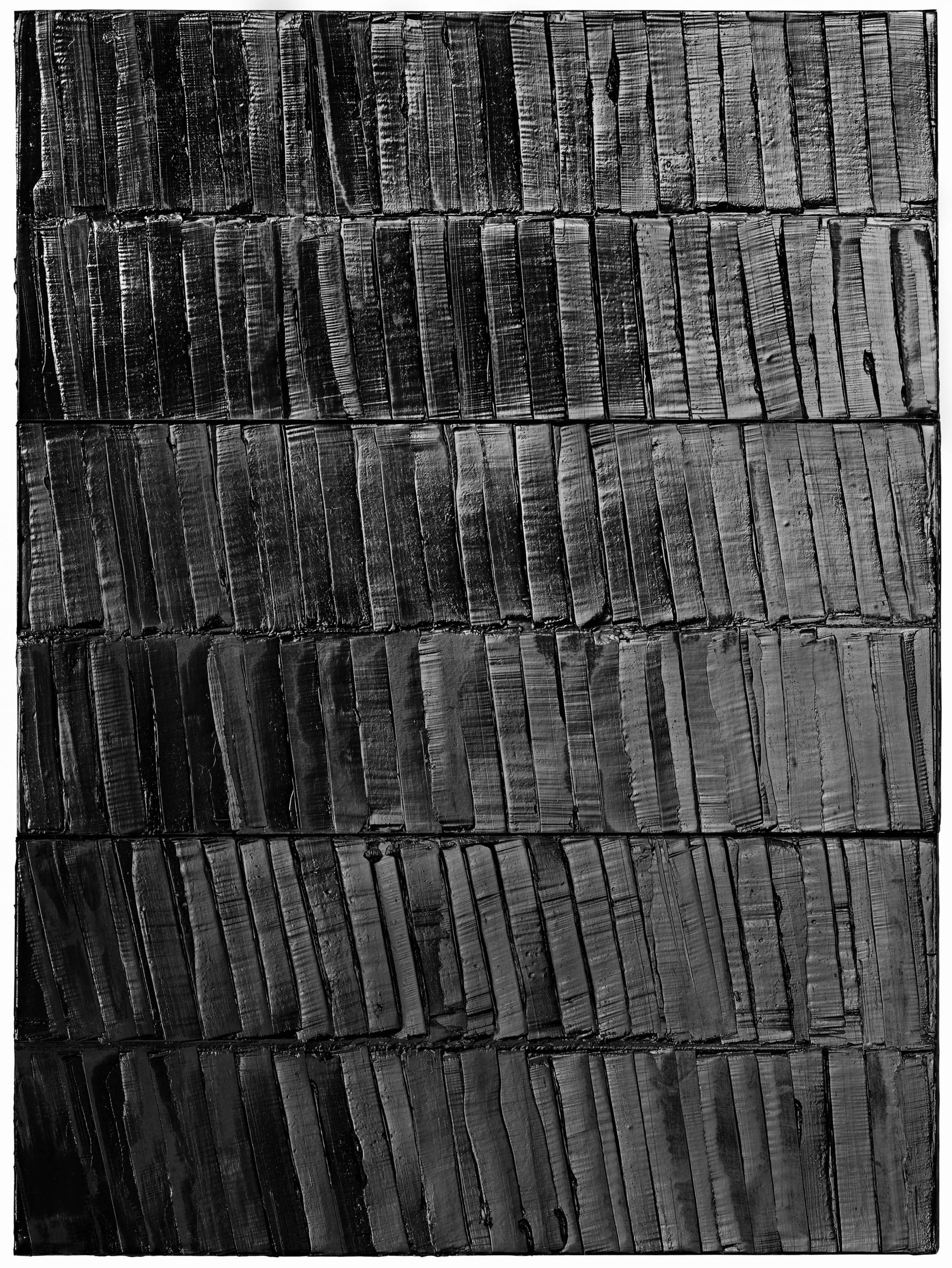

We are firmly convinced that architecture is perceived in a sensitive dimension which, in our opinion, is achieved through the use of authentic materials. We want to express simplicity, roughness and natural shades in full mass. They instil respect because they suggest that they have the capacity to last. Imperfections and slight variations strike a chord with us as they are humanising and a source of subtle vibrations. We believe that this approach develops all in once imagination, aesthetic sense and anchoring in reality.

The materials immediately and very often without us being aware of it, mobilise a mental image, a memory or an emotion. Ancient buildings are a good illustration of this extraordinary experience of materials as they tell us a sensitive story. They stimulate our senses in a global way: smells, creaking, piano playing, tapping, nuances, imperfections… They suggest weight, density, grain; you can judge by the eye their harshness or finesse. They are especially moving because you can see the craftmanship and the genius of the gesture that shaped them. Materials always evoke the anchoring in a territory, that of its know-how and its economic logic.

It is essential that we follow this sensitive and contextual thread using the construction techniques of our era. However, we are maintaining a certain distance from the construction industry that by nature produces standards: catalogues too easily guide towards preconceived and generic building models.

Our buildings are by nature prototypes and materials must serve a contextual purpose: it is a question of accuracy of their inclusion in an urban heritage that most of the time pre-exists. The genius of industry must therefore be used for the benefit of architecture.

To build our poetic visions, we have decided to improve our technical knowledge and especially our expertise in the production processes of materials, to encourage manufacturers to innovate. Our architectural choices target sobriety and a limited number of materials. Our work must hide efficiency, performance, standards and label. Is the quest for authenticity – which can be noticed in all fields – not finally expressing a need for reality that is inversely proportional to the increasing virtuality of our worlds?

Indeed, how can you feel good in the city – i.e. in the life of the city – when the architectural universe is outrageously repetitive, generic and poorly landscaped?

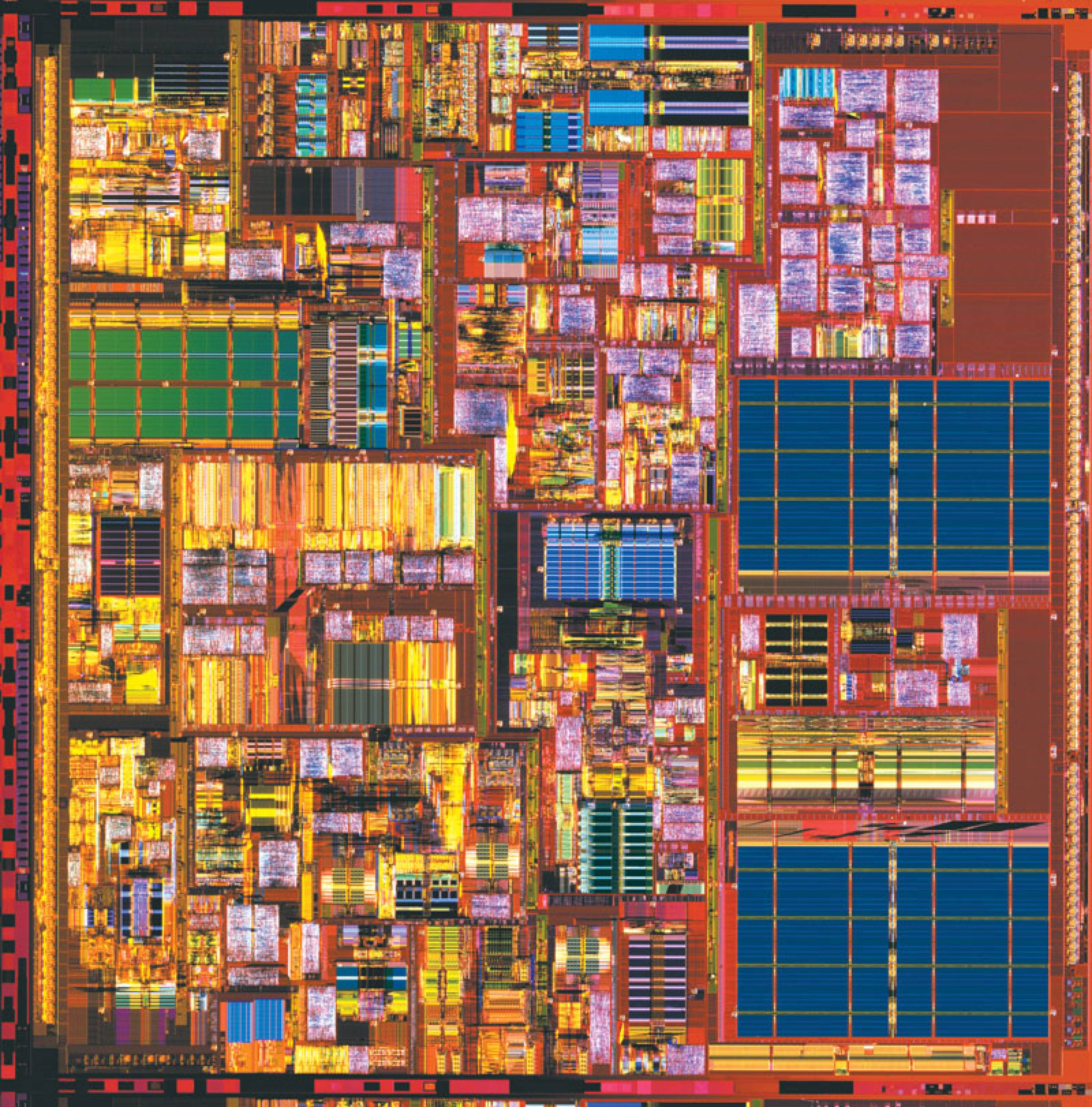

Besides the economic factors of the post-war period and the pressure for rapid construction, the very thinking of urban planning in the 1960s – despite the humanist inspiration of the Charter of Athens – failed to produce real cities, considering them more like some kind of machines.

Zoning choices, disconnection of the housing from roads and a distribution of buildings established according to large graphics amidst wide landscape areas could not create urbanity. In these neighbourhoods, buildings often seem to float in an endless network of public spaces. They are not well defined and very often they have no other use than parking stands.

De facto, the streets have been dramatically denied. However, in the streets, there is the pleasure of walking on the pavement, of going through sequences, of perceiving unusual details, smelling odours, of being immerse in the hustle and bustle of the city, of being solicited, tempted to enter a shop or a hall.

This is what the historic city offers in its dense mosaic of housing, activities and shops.

It facilitates and even imposes encounters, curiosity and discovery.

Let’s keep in mind the quality of the European city, appreciated for its capacity of mutation with an equal quality of architecture. And let’s introduce into our neighbourhoods the structure of the traditional city with its codes of density, variety, identity and resilience.

Inhabitants are expected to enjoy going through the places we imagine; this is how they will become involved in their neighbourhood.

The cumbersome heritage of the 14 million housing units that were globally badly built between the 1950s and the 1970s (and whose architecture has often become the unhappy identity of the neighbourhoods) reminds us of this requirement: It is not easy to throw away a building and replace it with the latest model.

Our society is both versatile and ultra-connected, it is constantly inventing new uses and searching for meaning. How can our buildings, which are built to last, stick as closely as possible to this changing reality?

They will surely have several lives and to be fully habitable, they have to offer reversible spaces, i.e. easily adaptable to new patterns or purposes.

From this point of view, isn’t the structure of the buildings the first act of sustainable development? In this respect, the amazing transformation capacity of the ancient workshops is particularly inspiring. Wide openings, simple and rasterised structures and open heights authorise a multitude of occupancy scenarios. These spaces are always characterised by a high degree of aesthetic coherence.

Building materials are the other obvious lever for the change of patterns we are looking for. Contemporary materials are not only hard to reuse but also, we no longer exploit local available resources (stone, wood, clay). It is also important to mention that many of the materials long promoted for energy performance are very poor (polystyrenes, PVC, glass wool, etc…). Technological escalation generates an embarrassing congestion: increasing number of air control devices, VMCs, air conditioning systems.

Isn’t contemporary industrial construction at the heart of this architectural paradox? Why using stone – whose carbon footprint is nil – is now considered an adventurous experiment? Isn’t it absurd that clay – an ancestral and available material – cannot be used just because it is not technically advised?

Given the prospect of a circular, non-carbon economy, only wood is currently making progress and opening up new perspectives.

Yet the new codes are full of austerity and happy frugality – as evidenced by the number of short circuit approaches initiated in the field of agriculture. We dream of an inhabitable world, fair and sober, in which recycling and reversibility would be regarded as a source of joy.

The obligation to use bio-sourced materials should profoundly change architecture, and it is within this promise that we want to set our action.